- Log in

-

- Sydney Overseas Office

- London Overseas Office

- Toronto Overseas Office

- Los Angeles Overseas Office

- New York Overseas Office

- Ulaanbaatar Overseas Office

- Dubai Overseas Office

- New Delhi Overseas Office

- Manila Overseas Office

- Jakarta Overseas Office

- Hanoi Overseas Office

- Kuala Lumpur Overseas Office

- Singapore Overseas Office

- Bangkok Overseas Office

- Map

- Sydney Overseas Office

- London Overseas Office

- Toronto Overseas Office

- Los Angeles Overseas Office

- New York Overseas Office

- Ulaanbaatar Overseas Office

- Dubai Overseas Office

- New Delhi Overseas Office

- Manila Overseas Office

- Jakarta Overseas Office

- Hanoi Overseas Office

- Kuala Lumpur Overseas Office

- Singapore Overseas Office

- Bangkok Overseas Office

Contents View

-

-

-

Laver: The Pioneering K-Food Captivating the World

-

02/20/2025

-

521

0

0

-

-

-

-

Laver: The Pioneering K-Food Captivating the World

When & Where

Laver is produced only in winter, with its peak season from November to March.

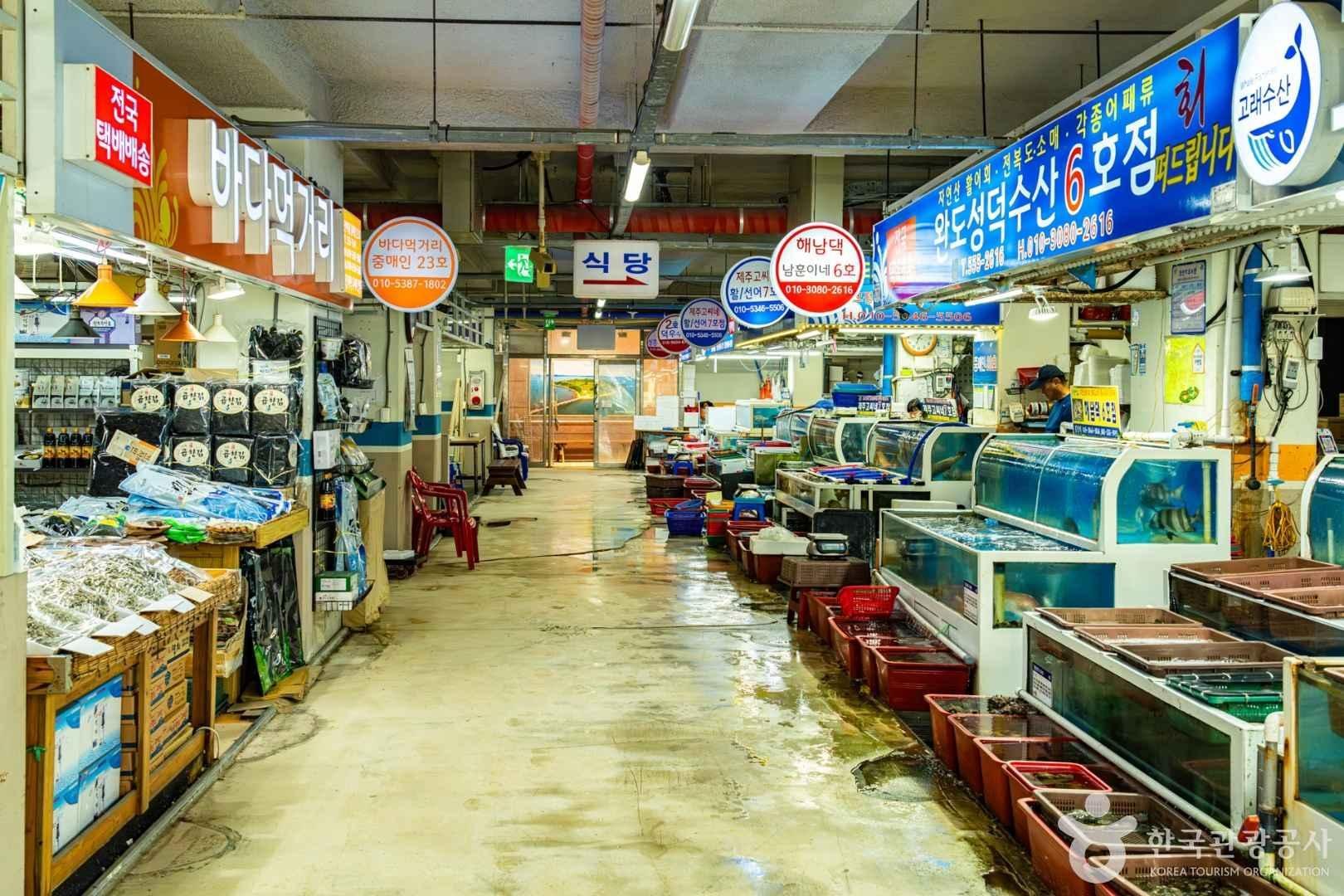

While laver can be easily found in supermarkets and restaurants, visiting Wando, which accounts for about 50% of the country’s laver production, allows you to taste more flavorful laver.

Laver, classified under the genera Porphyra or Pyropia, is a type of marine algae that is thinly spread and dried into a paper-like form, typically cut into square shapes for distribution.

Laver can be eaten by wrapping rice, like lettuce used for wraps, or as a side dish when dipped in soy sauce. Laver is also used in gimbap, a popular Korean dish in which various vegetables and other ingredients are rolled with rice and laver. Seasoned laver, lightly brushed with oil, toasted, and sprinkled with salt, is one of the souvenirs that travelers to Korea often purchase.

The Origin of Laver

According to the historical text Samguk Yusa, Koreans have been enjoying seaweed since the Three Kingdoms period. However, it wasn't until the 17th century that seaweed cultivation began. Legend has it that during the Byeongja Horan (Second Manchu Invasion of Korea) (1636-1637), a scholar named Kim (or Gim) Yeo-ik, who engaged in anti-Japanese activities, settled on Taein Island in Gwangyang, Jeollanam-do, and began to first to cultivate seaweed.

Laver (“gim” in Korean) was not called “gim” initially but was called “haetae” in the past, meaning the “grass from the sea." It is said that after Kim Yeo-ik’s successful cultivation of haetae, it was named “gim” in reference to the family name of the person who first successfully cultivated it.

Two Methods of Laver Farming

There are two main methods of laver farming. One is the “pole method,” and the other is the “floating method." In the pole method, wooden poles are driven into shallow waters, where laver spores are sown onto ropes and nets hung between the poles. As a type of marine algae, laver grows through photosynthesis. When the tide recedes, the laver receives sunlight to photosynthesize, and when the tide rises, it uses the stored energy to grow, enhancing its flavor and aroma. While growth halts when the laver is above water, this method yields high-quality laver known for its excellent taste and aroma, making it ideal for producing premium varieties.

On the other hand, the floating method involves attaching strings to floating devices, allowing the laver to remain at a consistent depth, regardless of sea-level changes. This method yields higher productivity, making it ideal for producing mid-range products to be consumed widely.

Types of Laver

The laver consumed in Korea is classified into two main types: itbadi dolgim (porphyra dentata) and bangsamuyeon dolgim (porphyra yezoensis). Itbadi dolgim is more commonly known as “gopchang dolgim” (meaning “beef intestine laver”) because its curled shape resembles beef intestines. Bangsamuyeon dolgim is the most widely available variety on the market. This laver looks like thin black paper, accounting for 70% of domestic production. Harvested bangsamuyeon dolgim can be processed thickly to be used to make gimbap or processed thinly and brushed with seasoned oil to make side dish.

The Evolution of Laver on Korean Dining Tables

Up until the 1980s, it was common to roast laver at home during the winter. The process involved brushing the laver with a mix of sesame oil and cooking oil, then roasting it one sheet at a time. This roasted laver was used as a side dish during winter or packed into school lunchboxes for children. Sometimes, the laver was roasted without oil and eaten by wrapping warm rice and dipping it into soy sauce.

Over time, the practice of roasting laver at home gradually faded, and market vendors took over. When you order laver at the market, vendors coat it with oil and roast it on the spot, attracting many customers with its enticing aroma. Even today, despite the wide variety of factory-produced laver, traditional markets still have stalls where you can get freshly roasted laver.

Recently, seasoned laver has become increasingly popular among consumers. This type of laver is prepared in factories with perilla oil, sesame oil, olive oil, and salt to enhance its flavor. Because of its clean packaging and ease of storage through an automated production process, it has gained widespread appeal. However, the oils used may oxidize when exposed to light, so the laver is sold in opaque packaging to maintain freshness.

Various Ways to Enjoy Laver

Koreans typically use laver as a side dish to accompany rice. It is common to place a sheet of roasted laver on top of warm rice or prepare it as gimmuchim (laver salad) or gimguk (laver soup).

Recently, laver has also become popular as a snack or appetizer. Gimbugak (laver chips), made by coating laver with sweet rice paste and frying it in oil, are a representative snack and side dish made from laver.

How to Make Gimbugak

- Ingredients: Dried laver, 200ml glutinous rice flour, 3 cups* water

*cup measurements refer to small paper cups, not the U.S. cup measure① Mix the glutinous rice flour with water and heat until it just begins to boil. Let it cool to make the sweet rice paste.

② Cut a sheet of dried laver into four pieces. Brush each piece with the glutinous rice paste and let them dry. You can sprinkle sesame seeds or red chili powder for extra flavor.

③ Quickly fry the dried laver in oil heated to about 170°C for 3-5 seconds.

④ Drain the oil and let the gimbugak cool.

In Wando, some restaurants offer gimguk as a side dish rather than a standalone item, often served alongside when abalone or sliced raw fish is served. Adding oysters to the gimguk in winter enhances its flavor and richness.

In addition, laver flakes are sometimes sprinkled over dishes like tteokguk (sliced rice cake soup) or noodles to add extra flavor.

Experience Information