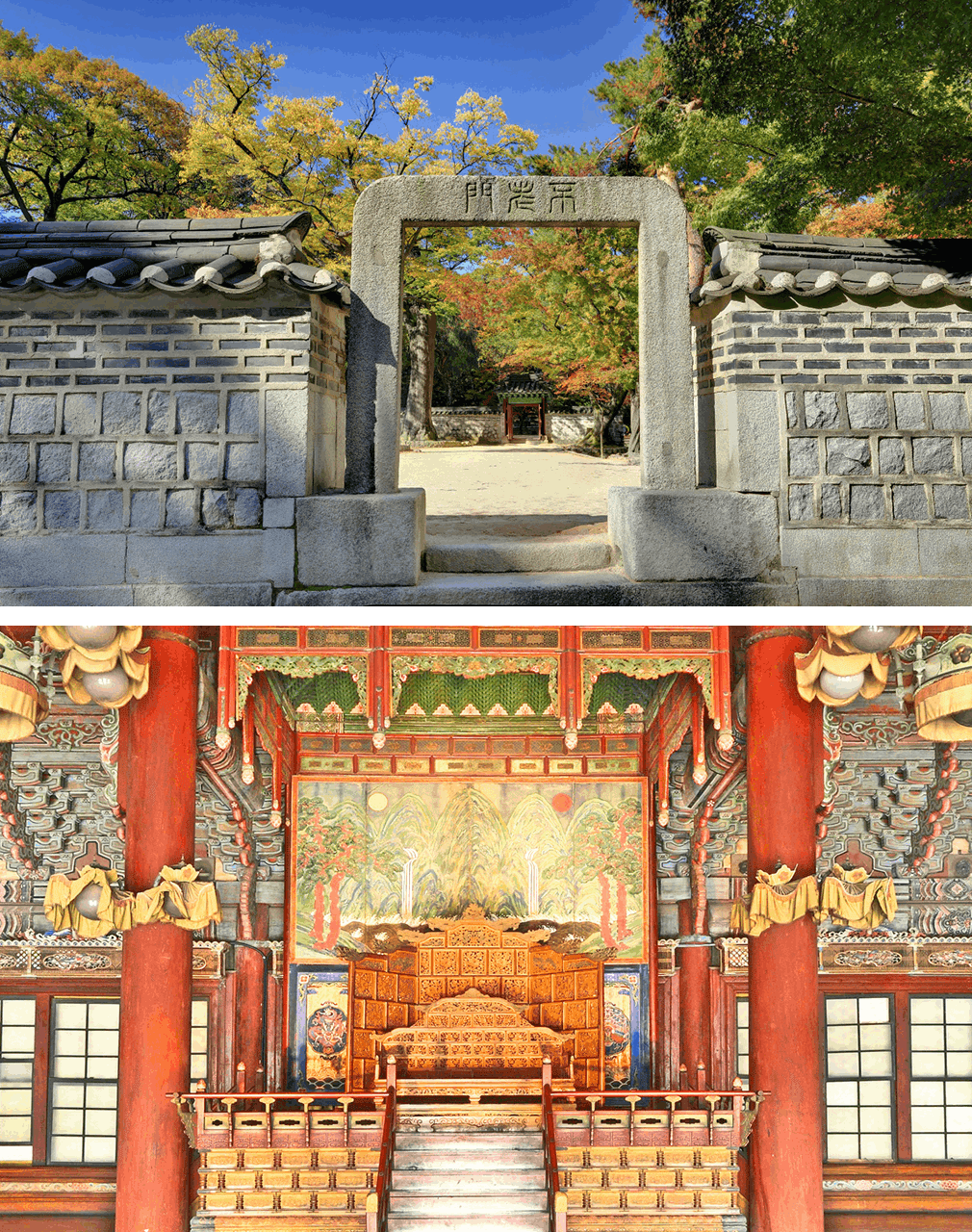

Changdeokgung Palace Complex

A Palace of Natural Beauty in Harmony with the Environment

Built in 1405, Changdeokgung was the secondary palace (where the king stayed during outings) to Gyeongbokgung, the main palace of the Joseon Dynasty and Daehan (Korean) Empire (1392–1910). Changdeokgung was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1997 for being an “exceptional example of [...] palace architecture and design, blending harmoniously with the surrounding landscape.”

Designers of Changdeokgung positioned its buildings using various contextual axes of nature in harmony with the area’s natural terrain, which is a different style from traditional palace architecture that lays out buildings symmetrically along the straight northsouth axis. For instance, the path from Donhwamun Gate (main gate) to its main hall (Injeongjeon Hall, where royal events were hosted and foreign envoys were welcomed), makes two turns, connecting the buildings aesthetically with the surrounding terrain.

It was named to mean “palace of illuminating virtue,” which was a Confucian ideal of Joseon. The names and layout of its buildings include such Confucian symbols and meanings. Reflecting pungsujiri (Korean geomancy) the buildings are laid out on flat grounds in the south while the gardens were arranged on hills in the north to harmonize with the topography.

Huwon Garden (also referred to as Secret Garden) maintained natural water pools, mounds, and rocks in the forest in their original positions to optimize their contributions to the landscape, and ponds pavilions, and buildings built throughout the garden harmonize beautifully and naturally with the surrounding. Huwon is recognized as the essence of royal gardening in the East.

Changdeokgung Palace was lost during Imjinwaeran, the Japanese invasion of Korea in 1592, but after a number of repairs and reconstructions, it came to serve as the official palace of the Joseon Dynasty for more than 250 years. Albeit reconstructed and expanded, its original design and form are preserved quite well, and the palace has had a huge effect on Korean architecture, garden and landscaping design, and related fields of art for centuries.

Cultural Heritage Administration, Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation, k-heritage.tv URL http://www.k-heritage.tv/main/en

Expedia

INFORMATION

Address: 99 Yulgok-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul

Phone: 02-3668-2300

Operating hours: 09:00–18:00 (Closed on Mondays)

Fee: 3,000won (Garden 5,000won)

Tour: Foreign language tours (English, Japanese and Chinese)

Web: www.cdg.go.kr

Transportation: 5-mimute walk from Exit 3 of Anguk Station, Subway Line 3; or 10-minute walk from Exit 7 of Jongno 3-ga Station, Subway Line 1, 3 or 5

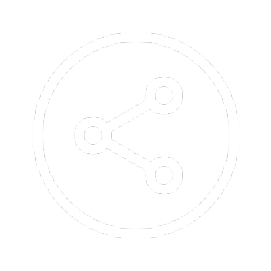

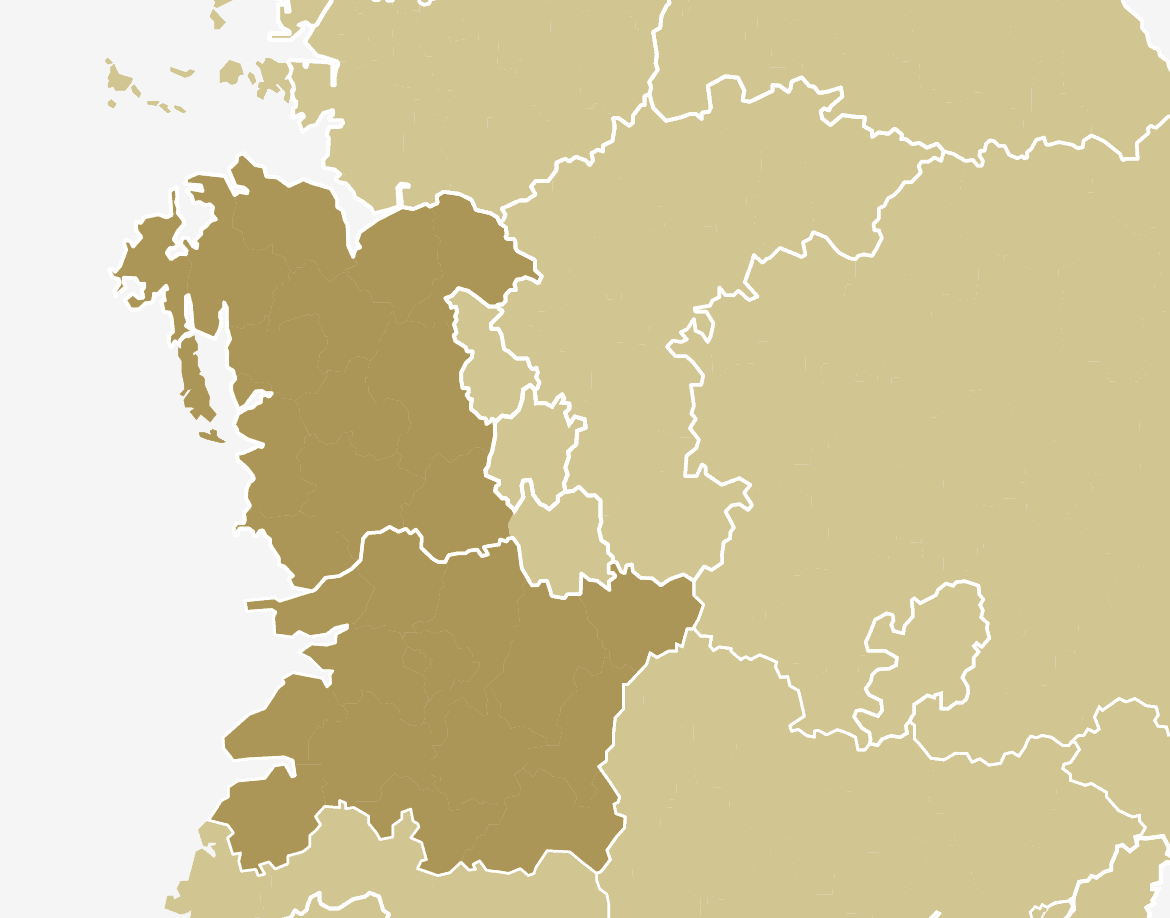

Located in the mid-western section of the Korean Peninsula, Baekje was one of the Three Kingdoms (57BCE– 668CE) of Korea together with Goguryeo in the north and Silla in the southeast. When Goguryeo attacked Baekje in 475, Baekje ended its Hanseong era, which centered on the Hangang River basin (current Seoul) and transferred its capital to Ungjin (current Gongju) to start Baekje's Ungjin era (475–538). Later, the capital was moved once again to Sabi (current Buyeo), and it is then that Baekje flourished as the Sabi era (538–660). In the late Sabi era, relocation of its capital was planned once again, and large Buddhist temples and a palace were built in Geumma (current Iksan).

Map of Baekje Historic Areas

Cultural Heritage Administration, Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation, k-heritage.tv URL http://www.k-heritage.tv/main/en

Gongju

Gongsanseong Fortress

Address: 53-51 Geumseong-dong, Gongju-si, Chungcheongnam-do

Phone: 041-856-7700

Operating hours: 09:00–18:00 (Closed on Seollal & Chuseok days)

Fee: 1,200won

INFORMATION

Baekje Historic Areas (Gongju)

Gongsanseong Fortress in Gongju and the Tomb of King Muryeong and Royal Tombs represent the Ungjin era. Built with a 2.6 km-long fortress wall, Gongsanseong Fortress was built to contain the royal palace. The Tomb of King Muryeong and Royal Tombs are comprised of the tomb of King Muryeong, the 25th king of Baekje (r. 501–523), and Tombs No. 1 to 6 of kings and royalties of Baekje. The Tomb of King Muryeong was discovered in 1971 in perfect condition with its tombstone and 5,232 artifacts. Reproductions of the royal tomb and excavated artifacts can be seen at the Royal Tombs Exhibition Hall.

Buyeo

Archaeological Site in Gwanbuk-ri and Busosanseong Fortress

Address: 229-16 Seongwang-ro, Buyeo-eup, Buyeo-gun, Chungcheongnam-do

Phone: 041-830-2880

Operating hours: 09:00–18:00 (Closed on January 1, and Seollal & Chuseok days)

Fee: 2,000won

INFORMATION

Baekje Historic Areas (Buyeo)

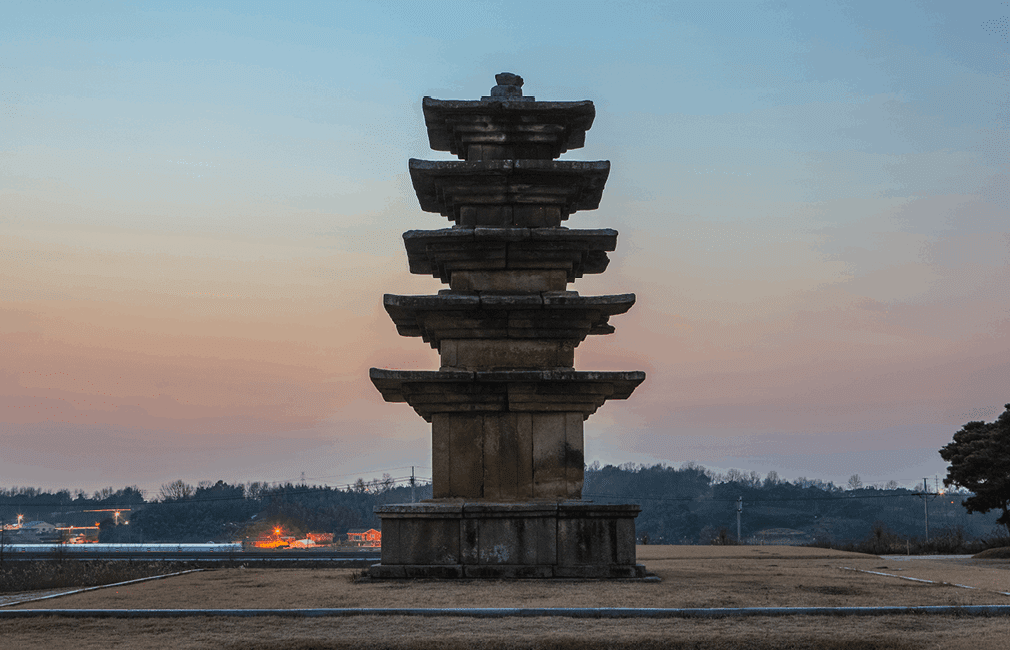

The Buyeo Royal Tombs, Busosanseong Fortress, Jeongnimsa Temple Site, Tomb of King Muryeong and Royal Tombs, and Naseong Fortress are proof of the Sabi era. The Archaeological Site in Gwanbuk-ri includes large buildings, underground storage facilities, and ponds. Busosanseong Fortress was built as the rear garden of the palace that also served as an emergency defense facility. Jeongnimsa Temple Site reveals a temple uniquely located at the center of the capital, and contains a five-story stone pagoda that shows the period when building materials of pagodas transitioned from wood to stone.

Naseong is the 6.3 km-long fortress wall constructed as an outer wall to defend the royal palace and mark the border of the capital city. Various construction methods were used. For instance, in mountainous areas, dirt was packed and piled and the exterior was finished with stones. In wetlands, the foundation was reinforced by driving tree branches, mud, and stakes into the ground. These construction techniques were later adopted in Japan. The Buyeo Royal Tombs (Tombs No. 1 to 7) outside of Naseong Fortress show a stone finishing method more advanced and improved from that of previous periods. Nearby is a temple site believed to be where families and friends went to remember and pray for the deceased. The Great Gilt-bronze Incense Burner of Baekje (National Treasure) excavated from the site is a masterpiece and a telling example of the fusion of Taoism and Buddhism, and the passion and technique of the master craftsmen of Baekje. It is on display at the Buyeo National Museum.

Iksan

Archaeological Site in Wanggung-ri

Address: Wanggung-ri, Wanggung-myeon, Iksan-si, Jeollabuk-do

Phone: 063-859-5875

Operating hours: 09:00–18:00 (Closed on Mondays, and January 1)

Fee: Free

INFORMATION

Baekje Historic Areas (Iksan)

Archaeological Site in Wanggung-ri, Iksan is the site of a royal palace built during the reign of King Mu (r. 600–641) in the late Sabi era. The site of a large building estimated to be the central building of the palace, living spaces such as a restroom, the rear garden, and the Wanggung-ri Five-story Stone Pagoda still remain to this day. King Mu built the massive Mireuksa Temple to embody the idea of Maitreya descending from the heavens to save the world. In the vast temple site, the Stone Pagoda at Mireuksa Temple Site (National Treasure) stands on the west side of the site. Initially built in 639, it was restored to its current form after 20 years of repair. It’s been told that King Mu, born Seodong, grew up under a single mother. He did everything he could to marry Princess Seonhwa of the Silla Kingdom (57BCE–935CE) and became king. This story of Seodong is reenacted annually at the Iksan Seodong Festival.

Seokguram Grotto was made of granite, and 38 statues, including that of the Sakyamuni Buddha at the center of the dome-style main room, were exquisitely carved on surrounding walls, antechambers and corridors. The Principal Buddha is sitting on a lotus flower-shaped pedestal with a mystical expression of kindness, gentleness and grandness. The hands of the Buddha are in Bhumisparsha mudra, which is the position to ward off temptations of the devil and touch the earth to prove the glory of Buddha. Flagstones on the wall behind the Principal Buddha play a role similar to that of a halo, adding grace and sacredness to the Buddha statue, and people can look up to the center of the antechamber.

Bulguksa Temple is comprised of three “kingdoms of Buddha.” With Daeungjeon Hall at the center, the pavilion, Cheonungyo and Baegungyo Bridges, and Dabotap and Seokgatap Pagodas make up the largest space that represents the world of suffering where Buddha resides. The space where Geungnakjeon Hall, Chilbogyo Bridge and Yeonhwagyo Bridge are located represents the Amitabha Buddha’s land of utmost bliss, and the space where Birojeon Hall and Gwaneumjeon Hall are located represents the Lotus Sanctuary.

Buildings were constructed by using coarse natural stones to build the stereobates and then stacking polished artificial stones on top in a well-balanced way to reinforce the buildings. The fact that Cheonungyo and Baegungyo Bridges are big and fancy, while Yeonhwagyo and Chilbogyo Bridges are small and simple, and the differently-styled Dabotap and Seokgatap Pagodas are proof of harmony and beauty of contrasts.

Seokguram Grotto and Bulguksa Temple in Gyeongju are ancient Buddhist sites created by Kim Dae-seong, the prime minister of Silla, from 751 to 774. Seokguram Grotto is comprised of a grotto built by applying elaborate mathematical and geometric principles and architectural techniques with a statue of the Sakyamuni Buddha and several reliefs that display an intricate sense of aesthetics. Considered the “Buddha Land,” Bulguksa Temple shows the uniqueness of temple architecture of ancient Korea through the harmonious structure and layout of wooden buildings with stone stereobates and stone pagodas.

INFORMATION

Bulguksa Temple

Address: 385 Bulguk-ro, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Phone: 054-746-9913

(Templestay 054-746-0983)

Operating hours: 09:00–17:00 (Year-round)

Fee: 6,000won

Web: www.bulguksa.or.kr

Transpotation: Bus no. 11 (15 minutes) from Bulguksa Station

Seokguram Grotto

Address: 873-243 Bulguk-ro, Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Phone: 054-746-9933

Operating hours: 09:00–17:00 (Year-round)

Fee: 6,000won

Web: www.seokguram.org

Transpotation: Bus no. 12 (20 minutes) from Bulguksa Temple

INFORMATION

Jongmyo Shrine

Address: 157 Jong-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul

Phone: 02-765-0195

Operating hours: 09:00–18:00 (Weekdays open for guided tours (English, Japanese and Chinese), Saturdays and national holidays open for regular admission. Closed on Tuesdays.)

Web: jm.cha.go.kr

Transportation: 5-minute walk from Exit 11 of Jongno 3-ga Station, Subway Line 1, 3 or 5

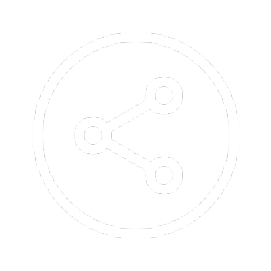

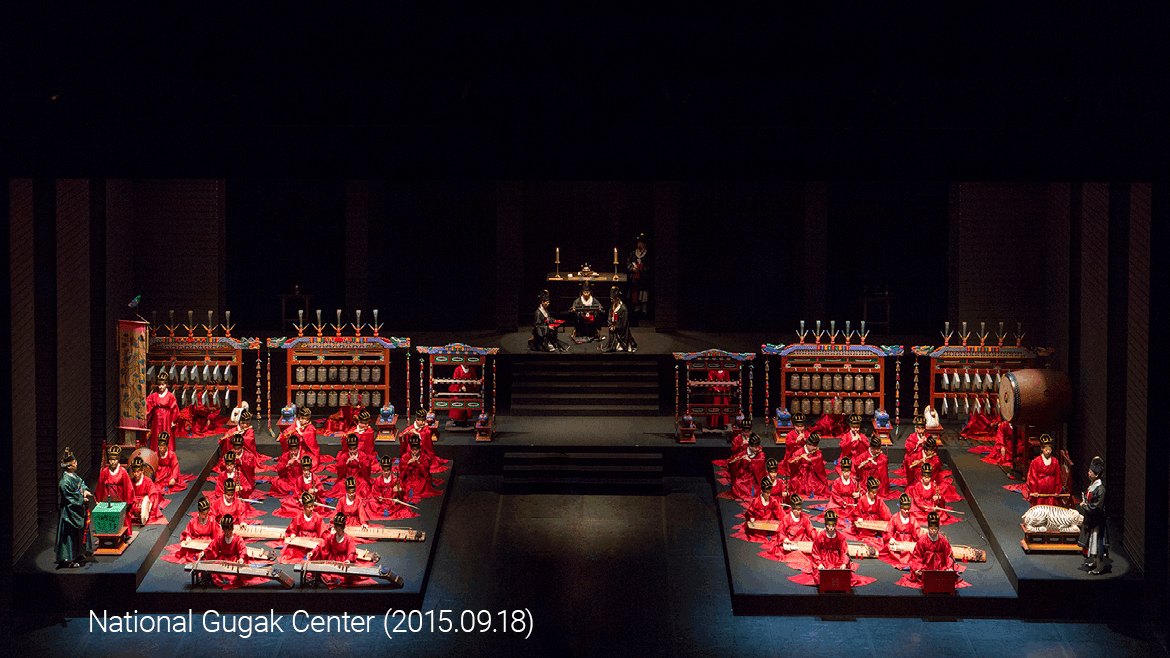

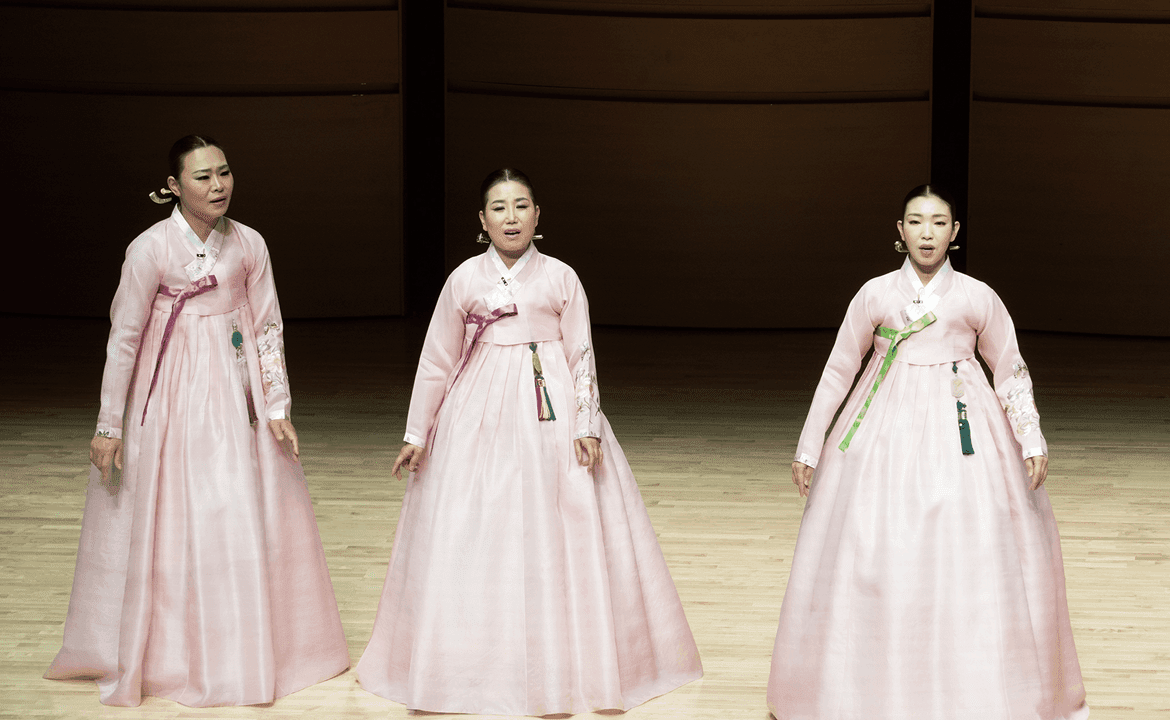

Royal Ancestral Ritual in the Jongmyo Shrine

Annually on first Sunday of May and first Saturday of November

National Palace Museum of Korea

The Royal Ancestral Ritual in the Jongmyo Shrine and its Music is a ritual offered to royal ancestors of the Joseon Dynasty and Daehan Empire that has been continued for more than 500 years. It is a national rite in which strict procedures are carried out with dances, songs and music at Jongmyo Shrine.

Started as a Confucian country, the Joseon Dynasty considered filial piety as the first duty for a person to fulfill and used it as the most important norm in ruling the country. That is why ancestral rituals showing filial piety to ancestors are especially emphasized. Serving as the national model, the Royal Ancestral Ritual in the Jongmyo Shrine is a grand and strictly organized event.

It is comprised of the following procedures: welcoming the spirits of ancestors, entertaining them with dance and music, and sending them back. When all participants, such as officials in charge of the ancestral ritual, musicians and dancers, are in their designated positions, the king burns incense to welcome the spirits. Afterward, food and liquor offerings were presented to entertain the spirits, then after clearing the table, the sprits are sent off.

Jongmyo Jeryeak is the ritual music played during all the procedures of the Royal Ancestral Ritual. At the reenactment held every May and November, Botaepyeong and Jeongdaeeup are played with traditional instruments. With percussion instruments, such as pyeonjong (carillon) and pyeongyeong (stone chime) leading, melody instruments, such as dangpiri (type of flute), daegeum (large transverse bamboo flute) and haegeum (two-stringed fiddle), and other instruments like janggu (double-headed drum), jing (gong) and taepyeongso (double reed wind instrument) are played. Along with the music, 64 dancers in eight rows dance with simple but powerful moves while carrying symbolic props such as piri (flute) and wooden swords to praise the king’s charitable deeds. The Royal Ancestral Ritual in the Jongmyo Shrine and its Music are regarded as a solemn and refined complete work of art.

Cultual Heritage Adbinistration X BIBIGO

Kimjang, also spelled as gimjang, is the tradition of making large amounts of kimchi to eat through the cold winter. Kimchi, or dimche as it was called in the olden days, is preserved vegetables seasoned and fermented with various spices and seafood. Kimjang is an old custom and living culture involving a family’s unique recipe for kimchi, which is passed down through generations. Families and communities are brought together through this annual event.

There are hundreds of varieties of kimchi, and regardless of the social class and region, kimchi is an essential part of the Korean meal table. Full of vitamins, minerals and lactic acid bacteria, this staple of the Korean diet is purported to strengthen the immunity of regular consumers and deliver lots of nutrients. Usually, kimchi is prepared frequently using vegetables in season, but to prepare for winter, when snow blankets the peninsula and vegetables are hard to find, large quantities of kimchi are made and preserved.

Kimjang used to be a year-long process, with regular duties for each season. In spring, each household made jeotgal by salting and preserving seafood such as shrimp and anchovies, by summer they bought bay salt and removed excess bitterness from it, then in late summer, chili pepper powder was made, and in late fall, a day when the weather was just right and everyone could get together for kimjang was selected. Kimchi hangari, which are clay pots used for storing kimchi, were also prepared and buried in the ground.

Kimjang concentrates on “whole cabbage kimchi,” which is made by adding various seasonings and condiments to whole heads of napa cabbage and mixing together. First, cabbages brined one or two days prior are thoroughly rinsed in water then drained. Next, a seasoning made of radish, green onions, mustard leaves, garlic, ginger, chili pepper powder, salted seafood (jeotgal) and other seafood are mixed and rubbed and spread between each leave. During kimjang, various other types of kimchi are also made in addition to whole cabbage kimchi, including dongchimi (radish water kimchi), which is made by fermenting radish in brine; pagimchi (green onion kimchi), made by seasoning green onions, and kkakdugi (diced radish kimchi).

Nowadays, as the family structure and housing culture have changed, most households buy their kimchi, instead of making at home. However, many communities and organization host various kimjang events and festivals to make great amounts of kimchi to be shared with elders and those in need. The Korean kimjang culture is a beautiful custom where neighbors get together and bond while sharing their kimchi and secret recipes. In addition, almost every Korean household owns a “kimchi refrigerator,” an electric appliance that only exists in Korea, to store kimchi for a prolonged time at a desired temperature and humidity.

KoreaFoundation

Jeongseon Arirang

Jindo Arirang

Miryang Arirang

INFORMATION

Arirang Museum

Address: 51 Aesan-ro, Jeongseon-gun, Gangwon-do

Phone: 033-560-3031

Operating hours: 10:00–18:00 (Closed on Mondays, January 1, and Seollal & Chuseok days)

Performances offered (2,000won)

Miryang Arirang Training Center & Exhibition Hall

Address: Miryang Arirang Center Annex 1st Fl., 112 Miryang daegongwon-ro, Miryang-si, Gyeongsangnam-do

Phone: 055-359-4527

Operating hours: 10:00–18:00 (Closed on Mondays)

Fee: Free

Web: www.mycf.or.kr (Korean only)

Transportation: 5-minute taxi from Miryang Intercity Bus Terminal

A representative folk song of Korea, “Arirang” was created by adding thoughts and words of numerous people over a long time and many generations. It is comprised of a chorus, “arirang arirang arariyo,” and two lines of short and simple lyrics. Because is easy to sing together, and anyone can create lyrics, it has been included in various music genres over the years.

Although the exact beginning and first lyrics are not known, it is estimated that there are more than 60 types and 3,600 folk songs titled “Arirang.” The representative ones are “Jeongseon Arirang” of Gangwon-do in the eastern part of Korea, “Jindo Arirang” of Jeollanam-do in the southwest and “Miryang Arirang” of Gyeongsangnam-do in the southeast.

“Arirang” became widespread throughout the nation after professional sorikkun (singer) began singing it as a popular folk song in the mid-19th century. Since then, many variations of the song were created, and one of the more popular ones was re-arranged and used as a theme song in Arirang, a movie that portrays the spirit of the Korean people produced by Director Na Un-gyu in 1926. As the movie became a huge success, the theme song also gained popularity nationwide, and became a song that comforted the souls of many as Korea went through a tumultuous history and people had to leave their homes and country.

“Arirang” is a song loved by all Koreans, regardless of class, and even among emigrants and their descendants, as well as foreigners residing in Korea. That is why it is called the “unofficial national anthem.” Even to this day, the song unites, communicates, and continues to be re-created for use in various art forms, such as music, cinema, musicals, dances, and literature.

4 : 20

3 : 24

2 : 35

Cultural Heritage Administration, Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation, k-heritage.tv URL http://www.k-heritage.tv/main/en

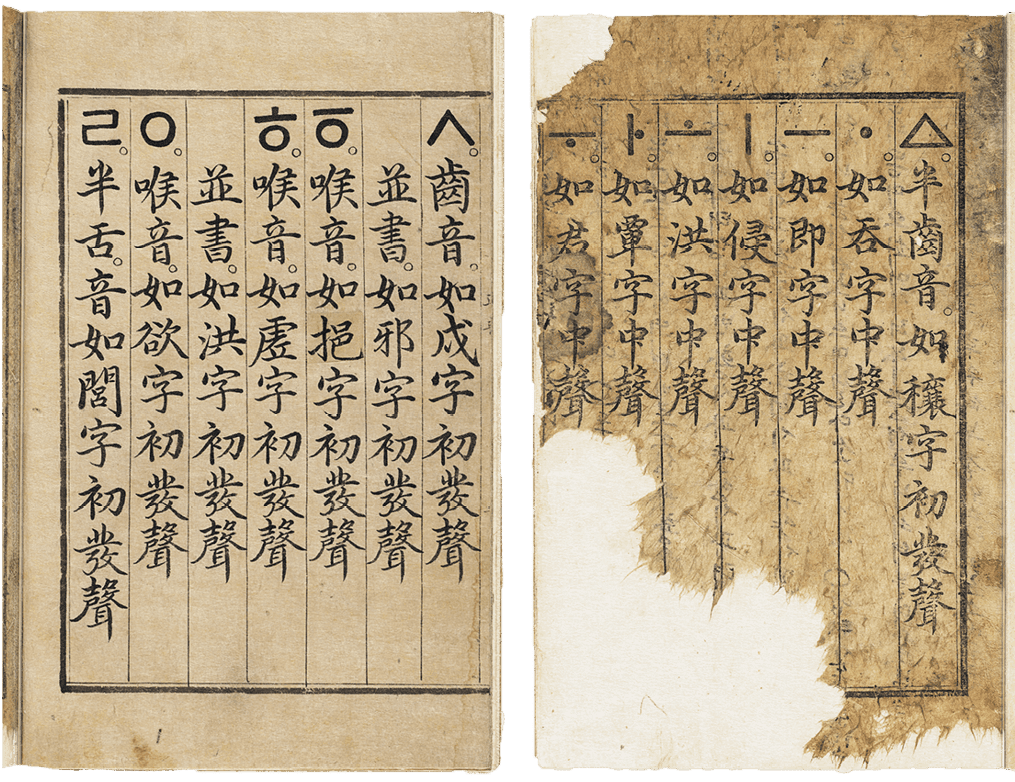

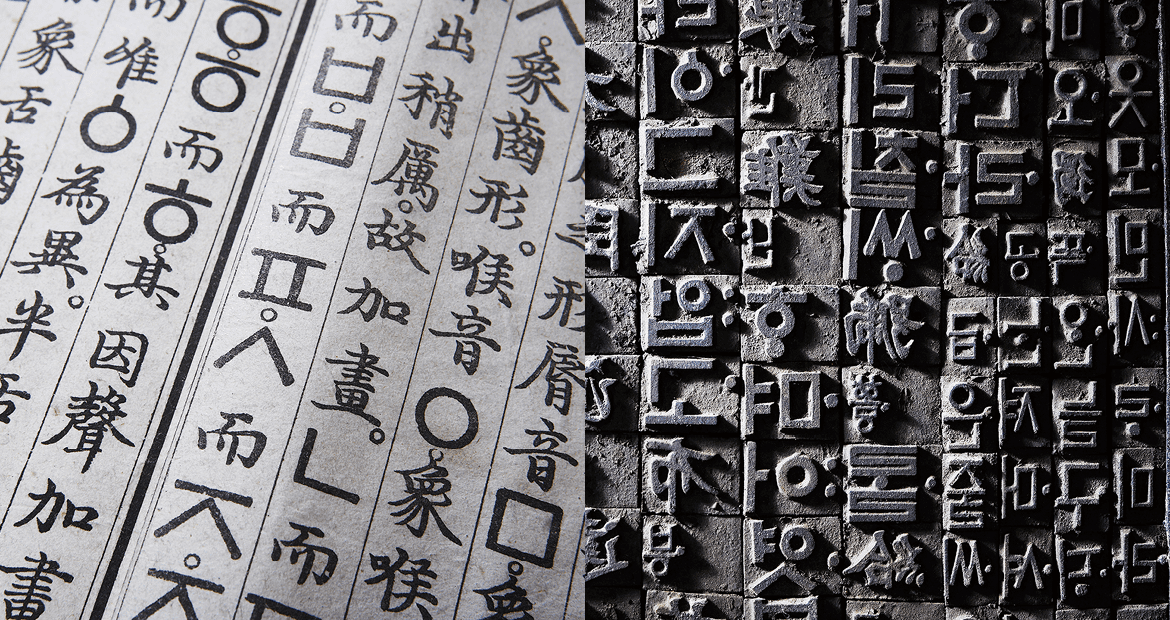

Hunminjeongeum Manuscript is a book that explains Hunminjeongeum, the Korean alphabet currently known as “Hangeul,” created by the fourth king of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), King Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450). This book clarifies who created the writing system, and why and how it should be read and written. It is the only record that contains explanations on how the characters of the Korean alphabet were intentionally created with a certain purpose.

Saddened at the fact that his people could not read or write, King Sejong created Hunminjeongeum, which means “proper sounds for the people,” and proclaimed it in September 1446 on the lunar calendar. Hunminjeongeum is a systematic phonogram in which sounds can be expressed in symbols by combining 28 characters comprised of 17 consonants and 11 vowels, and is easy for anyone to learn and write.

The Hunminjeongeum Manuscript is composed of “Yeui” (Examples and Usages), which contains the proclamation written by King Sejong himself, and “Haerye” (Explanations and Examples), containing detailed descriptions on “Yeui” by scholars of Jiphyeonjeon, the academic research institution at that time. “Yeui” is comprised of the purpose of creating Hunminjeongeum, and information about sounds and uses of the initial consonants and middle consonants.

“Haerye” is comprised of Jejahae (explanation of the principle of Hunminjeongeum), Choseonghae (explanation of the initial sounds), Jungseonghae (explanation of the medial sounds), and Jongseonghae (explanation of the final sounds), and also Hapjahae (explanation on how to combine two to three sounds to make a character), and Yongjarye (examples of 123 words using the letter combination method). The account of writing “Haerye,” and characteristics and advantages of the new Korean alphabet are briefly explained in the introduction at the end.

NATIONAL HANGEUL MUSEUM

INFORMATION

Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies at Seoul National University

Address: 1 Gwanak-ro (Building no. 103), Gwanak-gu, Seoul

Phone: 02-880-5317

Operating hours: 09:30–17:30 (Closed on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays

Fee: Free

Web: kyu.snu.ac.kr

Transportation: Shuttle bus or bus no. 5511 (20 minutes) from Exit 3 of Seoul Nat'l Univ.

Station, Subway Line 2

Oegyujanggak Uigwe

(Uigwe at the Records House of Archives)

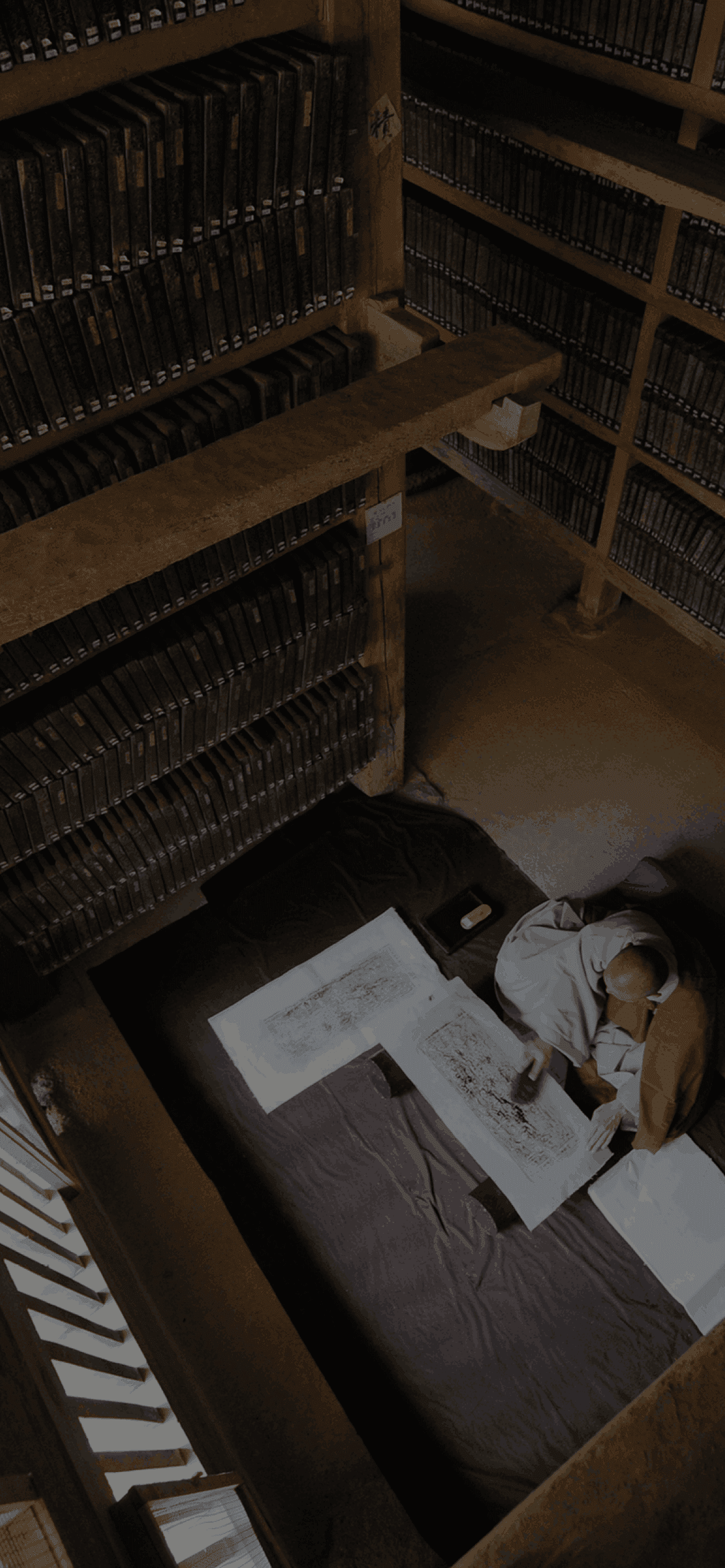

Uigwe: The Royal Protocols of the Joseon Dynasty are books that summarized major events of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) through texts and illustrations, and events are categorized by period and theme. The books produced in early Joseon were lost in fires during Imjinwaeran, the Japanese Invasion of Korea (1592–1598), but more than 4,000 books from the 17th century to 20th century still remain. The 2,940 books of 546 categories housed in Seoul National University’s Kyujanggak, and 490 books of 287 categories stored in the Academy of Korean Studies were added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.

The royal family of the Joseon Dynasty left records of special events like coronations, marriages and funerals of kings and queens, as well as regular events, such as entertaining foreign envoys, so that later generations could refer to them. In Uigwe, the entire process of an event, including list of staff members, number of employees, work allotment, list of used items, and expenses, were all recorded in detailed texts and illustrations.

Banchado and Doseol, both illustrated depictions of events, offer a lively written and three-dimensional visual accounting of the events. In addition, the texts and illustrations also reflect the era, showing lifestyles of the time.

Five to nine manuscripts or printed copies were made for each Uigwe. The king’s copy, called “Eoramyong,” was different from other copies, which were produced to be divided and stored in major government offices or historical archives. Only one copy of each Uigwe was made for the king. They were produced on high-quality paper with a silk cover and decorations, and palanquins, ceremonial objects as well as facial expressions were more detailed and colorful.

Uigwe is also a record that preserves past legacies of the Confucian society, the dominant ideology in East Asia at that time. Confucianism put special emphasis on ceremonials and rituals as a tool to rule the people and maintain social order. The universal philosophy of Confucianism can be seen through the books that documented national ceremonies of the Joseon Dynasty, which used Confucianism as its ruling principle.

Wonhaeng Eulmyo Jeongni Uigwe

This Uigwe records the 60th birthday ceremony of Crown Princess Hong, the mother of King Jeongjo (r. 1776–1800). It depicts the celebration held in 1795 at Suwon City Wall (today's Hwaseong Fortress), as well as the construction and installation of a pontoon bridge on the Hangang River for the procession.

Yeongjo Jeongsun Wanghu Garyedogam Uigwe

This Uigwe details the wedding of King Yeongjo and Queen Jeongsun, his second queen, in 1759. The 50-sided illustration depicts a 1.5 km parade comprised of 379 horses and 1,299 people.

Banchado

This painting shows government officials lining up in an orderly manner for an event. Portraying an aerial view of the march, it provides an overall view of the entire venue.

Donguibogam:

Principals and Practice of Eastern Medicine

Encyclopedia of the Oriental Medicine that First Reflected the Concept of Preventive Medicine

Donguibogam: Principals and Practice of Eastern Medicine is a medical book comprised of 25 volumes and 25 books that Heo Jun (1539– 1615), the primary doctor to King Seonjo and King Gwanghaegun of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), wrote from 1596 to 1610. The book is a compilation of more than 2,000 years of Eastern medical knowledge from China and Korea, and experiences in diagnosing and treating patients. It was printed using wood type in 1613.

Even though Donguibogam was a book that systemically covered professional medical knowledge and techniques, it was also the first book that considered the public’s use of it for medicinal purposes. Rather than declaring the illness, it allowed the reader to look up the body area that hurt or ached, and introduced easy-to-find medicinal herbs and simple treatment methods in easy vocabulary. It was written mostly in Hangeul (Korean alphabet) so that even commoners could read and use the book.

It is comprised of five chapters: “Naegyeongpyeon” dealing with internal diseases, “Oehyeongpyeon” about external diseases, “Japbyeongpyeon” on acute and miscellaneous diseases including epidemics, “Tangaekpyeon” about medication, and “Chimgupyeon” about acupuncture and moxibustion. The theory, prescription and references for a disease are organized in each chapter. Donguibogam is also significant in that it was the first medical book that reflected Yangsaeng, the concept of preventive medicine, in medical science.

Yangsaeng in Donguibogam regards a person’s disease as a result of a combination of physical, social and psychological factors and therefore, emphasizes the benefit of a healthy lifestyle to prevent a disease rather than focusing on treatment. This is an argument more than 200 years ahead of modern medicine’s emphasis on preventive medicine. Donguibogam is also the only medical book among UNESCO’s Memory of the World.

INFORMATION

National Library of Korea

Web: www.nl.go.kr

Heo Jun Museum

Address: 87 Heojun-ro, Gangseo-gu, Seoul

Phone: 02-3661-8686

Operating hours: 10:00–18:00 (Closed on Mondays, January 1, and Seollal & Chuseok days

Fee: 1,000won

Web: www.heojun.seoul.kr

Transportation: 10-minute walk from Exit 1 of Gayang Station, Subway Line 9

Seoul K-Medi Center

Web: kmedi.ddm.go.kr

Daegu Yangnyeongsi Museum of Oriental Medicine

Web: www.daegu.go.kr/dgom

Ebook

Head Office

Address: 10 Segye-ro, Wonju-si, Gangwon-do 26464, Republic of Korea

Phone: 82-33-738-3000

Web: kto.visitkorea.or.kr

Web: visitkorea.or.kr

Overseas Offices

Americas

Los Angeles

New York

Toronto

Oceania

Sydney

Europe

Frankfurt

Paris

London

Moscow

Vladivostok

Asia

Singapore

Bangkok

Taipei

Kuala Lumpur

Dubai

New Delhi

Hanoi

Jakarta

Manila

Istanbul

Almaty

Ulaanbaatar

China

Beijing

Shanghai

Guangzhou

Shenyang

Chengdu

Xian

Wuhan

Hong Kong

Japan

Tokyo

Osaka

Fukuoka